You must concentrate upon and consecrate yourself wholly to each day, as though a fire were raging in your hair. Taisen Deshimaru

My wife believes that I have an obsessive attachment to stones. I began collecting rocks in childhood, gathering stream-polished pebbles that I carefully stashed in my pockets. After we inherited the farm business nine years ago, a wholesale cut flower farm, I graduated to the larger stuff, piling boulders and fieldstone all around our homestead. Now I drive a skid steer loader, turning compost and moving wood chips, and, when I find a free moment, I lift a few large stones too. While I enjoy the challenge of moving big rocks the old way, by pry-bar and fulcrum, hydraulic forklifts make quick, safe work of lifting boulders. Eventually, I hope to complete many stonework projects – a Japanese dry-stone garden, retaining walls and pathways – but the busyness of family, farm work and aikido often make landscaping an elusive pursuit.

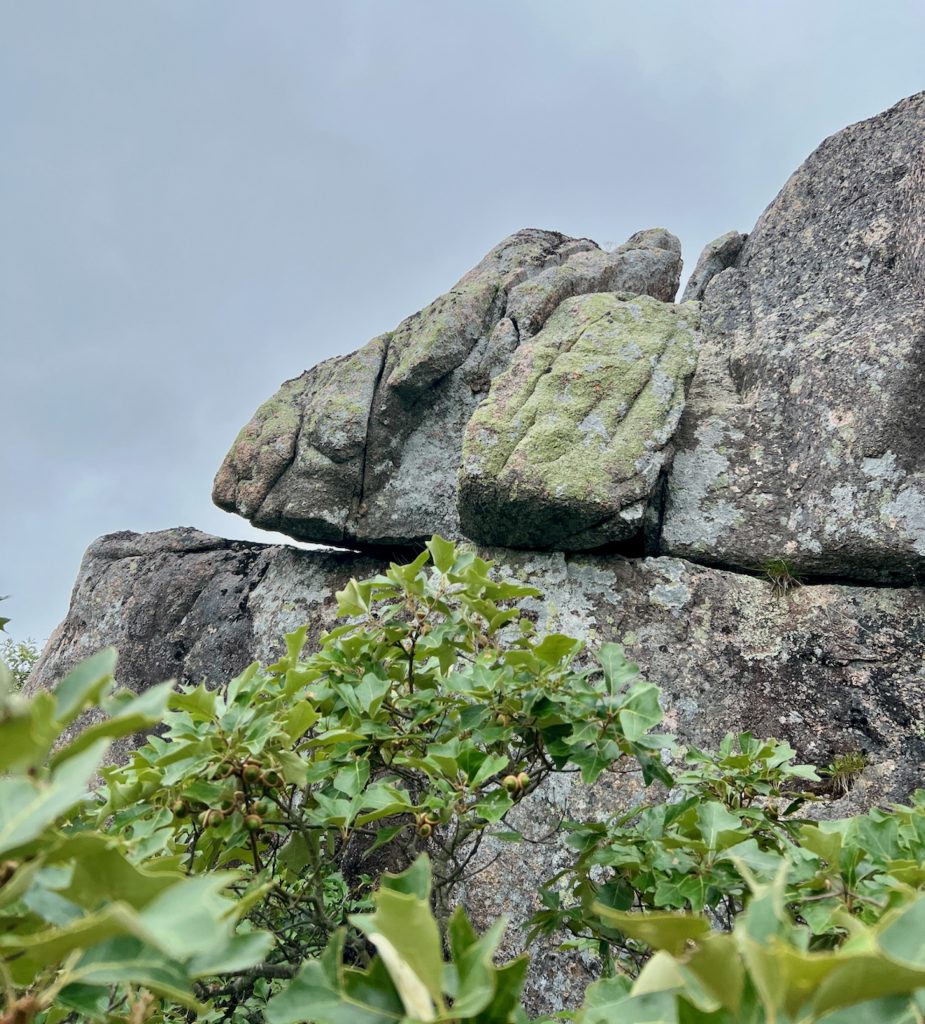

Boulder hoarding reflects my consumerist mentality; all Americans like bargains, and with stones, at least of the non-lapidary sort, you get good weight to the dollar. Really, the truth is deeper: I am drawn to the gravitas, solidity and the sentience of rocks. In an uncertain world, nothing seems more stable, more rooted, than the miniature orogeny of stone; veins of quartz evoke worn footpaths of wild creatures and the tumble of water over cliffs.

On our farm, my stone hills continue to grow, popping up here and there, mushroom-like. Despite the blackberry brambles claiming the rock piles, it is hard to conceal them. Concerned about my rock collecting habit, Heidi taped a cartoon to the wall of our mudroom,[1] which I discovered returning home after one night teaching aikido. The drawing shows a cave couple in a cavern crowded with boulders. A volcano smolders in the distance. The man tells his cave partner that “I thought getting bigger rocks would make us happier, but I guess I was wrong.”

In matters of the heart she is invariably correct. Some years back I purchased the remnants of an old barn foundation sold by a farmer eager to make a profit from nothing. Over 18 yards of crumbly schist, soil and barn trash arrived by dump truck. While the stone is flat on two sides, usable for building retaining walls, it is impossible to break cleanly, shattering under the chisel. I guess I should have tested the stone with a few taps of my masonry hammer before purchasing it, the stone age version of kicking tires on the tractor or examining the teeth on the old work horse up for sale.

Worse still, the stone pile came with its very own rat colony. My Norway rat nursery is a textbook example of how desire leads to greater suffering, although our dog, Fern, disagrees: she takes great pleasure in hunting rats, and shows only a fleeting melancholy at the curious absence of movement after the kill (I should mention that Fern and our native coyotes finally solved the rat problem). And, increasing the ignominy of my funky rock investment, frozen ground and December snows delay stonework projects until next year. As snow obscures stone and ice roots boulders to the ground, I can only gaze at the pile of snowy schist and dream of future projects.

For a book lover, the next best thing to stacking stone is to read about it. Unfortunately, stone garden design is fraught with danger far greater than rats or a herniated disk. In the book Sakutekei (“Records of Garden Making”), the 11th century manual of Japanese gardening, we find a grim warning:

Regarding the placement of stones, there are many taboos. If so much as one of these taboos is violated, the master of the household will fall ill and eventually die, and his land will fall into desolation and become the abode of devils.

In my ignorance, I thought stonework would provide a meditative reprieve from the busyness of a working farm and homestead. Instead, I face death, desolation and demonic possession!

Written during the Heian era (794-1184), Sakuteiki emerged from a time when Japan transformed Chinese and Korean art, culture and religion into an aesthetic whole that reflected a uniquely indigenous spirit. Many rituals and taboos in modern Japanese culture, from garden design to the aikido dojo, originated during this dynamic period in Japanese history.

The concept of imi – taboos – reflects the convergence of Shinto animism, Chinese geomancy, and Buddhist tradition. In our skeptical age, it is easy to view superstition and rituals as products of an archaic culture. Old rituals may seem irrelevant to the physical practice of aikido; to many students, tradition is oppressive and backward thinking, like the weight of stone upon earth. In this purportedly rational age, do arcane traditions have value? Are ritual and taboo an integral part of modern aikido?

To answer these questions, let’s examine a few traditions practiced in the modern dojo. In pre-war Japan, tachigui – eating while standing – was frowned upon. However, after Western fast-food culture invaded Japan, tachigui lost much of its negative connotation; today, you can slurp hot noodles in broth at a ramen noodle shop, no seats in sight. In contrast, a dojo, whether it is dedicated to tea ceremony or to martial arts, emphasizes the formality and grace of old Japan. We sit when we eat, savoring each bite of food as a sacrament that nourishes and sustains our very lives. Ritual and taboo remind us that the dojo is a sacred space, fundamentally different from the outside world. The sense of otherness cultivated by mindful engagement with ritual gives practice a spiritual weight and focus.

In the dojo, four flowers in an ikebana arrangement are also taboo. When I was 13, shortly after I began aikido, Kanai Sensei explained that the bouquet containing four flowers on the kamiza would result in a death in the dojo. The chastened student removed the offending flower, but Sensei’s warning added a frisson of excitement to my practice because I was just learning high falls, which seemed sufficiently challenging, even without mortal danger due to sloppy floral design. Four flowers are bad luck because “Shi” is a homophone in Japanese for the word “death” and the number “four” (it is good to remember this particular imi because one should never purchase a gift of four items for a Japanese friend).

In Japan, four items are not only imi in the wrong context; traditional aesthetics and design also promote odd numbers and asymmetry. In garden design, asymmetry allows the stoneworker to cultivate naturalism in rock arrangements; the artist may create a sanzen (three mountain)[2] grouping of three stones, or perhaps 5 rocks, and so on, always placing odd numbered clumps of stone that evoke a small mountain range or islands emerging from a gravel ocean. Irregular design patterns imitate the disorder of rocks in the wilderness, where symmetry is uncommon. Obvious patterns or an especially dramatic contrasting stone draws the eye to the particular and unique rather than emphasizing our interconnectedness with nature.

The wild, naturalistic garden reminds us that we are not solitary creatures moving through empty space. Instead, we are an integral part of this interrelated natural landscape of mountains and rivers, a place of pulsating energy and complexity. In the Shinto tradition, everything is alive: even stones are sentient, containing unique kami – divine spirits. In Sakuteiki, the author encourages the gardener to “follow the request of the stone” (ishi no kowan ni shitagahite); stones are animate and have opinions regarding placement. While you may not believe in animist cosmology, skeptics can remind themselves that rocks on a molecular level are in continuous movement, and the dense diamond contains more empty space than one perceives with the human eye. The world is vast, mostly empty, and vibrating with tremendous energy and movement. Animist perception captures the spirit of quantum dynamism better than the jaded vision of a contemporary observer, who may see a stone as something inert and independent of the viewer, and therefore unworthy of deep awareness or respect.

Imi and ritual etiquette – reigi in Japanese – distinguish practice as something extraordinary, a conscious journey from our distracted quotidian selves into a unique realm of focus and presence. When we enter the dojo, we bow at the threshold: we have arrived at the border in which we commit ourselves to transformation through practice. The bow is an intentional, formal entry into a sacred space (dojo literally means “place of the way”- or spiritual path). Of course, this sense of entering a unique place only happens if the aikido student believes in the gravity and import of the bow. Faith is essential! We also learn by example, internalizing reigi through the physical practice of aikido, and filter our perceptions through our developing integration of body and mind. One of my most powerful memories of my aikido teacher, Chiba Sensei, was watching him bow at the memorial for Kanai Sensei’s passing: completely present and integrated within his movement.

Sometimes when I bow I practice a single breath, gently exhaling as I bend at the waist, pausing in my breath to contain a momentary sense of emptiness, and then, holding that stillness, I inhale slowly as I return to an upright position. Other times, I envision the bow as a release of ego: I am nothing before this practice, and nothing before my students. The bow is a surrender of independence, a recognition that we are humble and vulnerable, and our lives are contingent on our relationships to each other.

Of course, there is a difference between habitual etiquette and mindful embodiment of humility. Bowing is such an established habit that I sometimes bow at secular doorways, too: the local hardware store, or the Thai restaurant. I feel a bit embarrassed -did anyone see the dip of my torso before I catch myself? Should we express deference in the face of things greater than ourselves, like the tremendous burn of little Thai chili peppers? The heat of peppers is like the slap of the keisaku[3] during zazen. “Wake up!”

Etiquette, or rei, can save our lives, or at least grant us some sense of space and freedom in difficult times. John Prine sings:

Just give me one thing

That I can hold on to

To believe in this livin’

Is just a hard way to go

Imagine yourself as a samurai, about to go into battle. Death is inevitable, preordained: it is your karma as a warrior. How would you prepare? Where do you place your mind? A deep bow, a prayer, or perhaps the slow, methodical dressing of armor protects you by granting a reprieve of sorts, a sense of quietude that provides courage and solace in your darkest hour; just one thing to hold on to – in this fleeting world, we seek stability, the feeling that, like a boulder, we are grounded deep into the earth. By believing in the power of reigi – the spiritual force of ritual- the martial artist prepares for an uncertain future, and moves into the unknown with a bit less fear and uncertainty. Thus, etiquette and imi remain an integral part of our martial arts practice, providing structure and clarity in an uncertain world.

Before we become high priests of righteous reigi, it is good to remember that etiquette is the raft, not the goal. If we are too attached to ritual and discipline, rigidity of form leads to priggish elitism that enhances the ego rather than allowing us to learn in a spirit of genuinely open, reflective self-inquiry (and yes, I speak from personal experience!). There is the cautionary story where the Zen monk spends hours carefully raking leaves from the delicate moss near the temple. Proud of his labors, he watches the Roshi who examines the work for a brief moment, then proceeds to shake the nearby cherry trees so brown leaves fall once again, partially obscuring the emerald moss below. Sometimes, perfection is messy. And often, true beauty appears at the margins, partially hidden from view. This story also reminds us that the best instruction in proper form happens through a students’ attentive observation, illustrated by silent example rather than pedantic lesson.

I seek the right balance between irreverence and discipline. In the dojo, I always sit when I eat, so as not to break the taboo of tachigui. I try to sit down when I eat at home, too. It seems like a good practice because mindful eating prevents me from devouring a full package of corn chips at one sitting. I often realize that I don’t really want to eat the chips in the first place – I am just procrastinating because I am at an impasse with this essay. I realize that my desire for snacks was really a distraction, part of the endless desire-stream, like acquiring more boulders (however, I make an exception when I eat wild berries. Somehow, it doesn’t seem right to sit down and eat; I prefer to forage like a wild animal, shambling, bear-like, from one blueberry patch to another. Becoming a bear is the reigi of foraging).

The weight of stone welcomes eternity. It’s easy to toss faded flowers in the compost pile, but try moving one-ton boulders set deep into the hillside. Perhaps that explains some of my hesitation to create my drystone garden, so I build retaining walls, which rarely awake the wrath of kami. I remind myself that what is truly unique about traditional Japanese stonework is that it attempts to capture or harness the magic and vitality of the wilderness. Taboos don’t only provide boundaries and limit our freedom: we also discover a wonderfully playful spirit of the living landscape. In Sakuteiki we read:

The stones at the base of a mountain or those of a rolling meadow are like a pack of dogs at rest, wild pigs running chaotically, or calves frolicking with their mothers.

How delightful! Rocks are alive and the world is at play in all of its complex interrelationships. I hope that my amateurish attempts at stone work express my gratitude for working with the stuff and stones of this wild, precious world.

Snow falls on Cloud Mountain. It obscures siltstone, blankets schist and shale. Under the weight of snow, everything is washed clean. I imagine winter stones vibrating with molecular movement, but at a slower pace. The kami – the divine spirit within stone – sleep until I provide them with a new home in my rock garden in spring. Everything is alive, to be treasured, respected and treated with grace and care. I can certainly bow to that.

Gassho (palm to palm),

Cloud Mountain,

New Year’s Day, 2024

Takei, Jiro and Marc P. Keane Sakuteiki: Visions of the Japanese Garden. Boston, Tuttle Publishing, 2001. This translation contains a fascinating introduction in which the authors discuss the role of geomancy, Shinto and Buddhist beliefs in the development of Japanese aesthetics.

[1] Mudrooms are entryways to old Vermont farmhouses where families and dogs wipe muddy boots and paws before entering the main rooms of the house.

[2] Interestingly, triad stone groupings are also called Buddhist Trinity stones, with one tall stone in the back, flanked by two attendant stones.

[3] Keisaku or kyosaku is a flat wooden staff used in zazen (Zen meditation) in order to correct the meditator’s posture or inattention by striking it firmly on the person’s back. Or the meditator can request such a strike in order to regain one’s focus and clarity. Like spicy food, sometimes the brisk slap causes the recipient to break into a sudden sweat.