When I was 4 years old, I almost drowned. It was winter, and there was a great hole in the ice on our pond. I recall pushing my golden retriever, Tapper, away from the water’s edge; I was worried that he might break the ice, and instead I managed to propel myself into the water. I wore winter boots and a heavy parka, and didn’t know how to swim. I went under, into the icy blackness. I desperately struggled to get above the surface and breathe; nothing else mattered – all I wanted was to breathe the cold air.

Sometimes, when my mind wanders, I return to that moment. The memory of the proximity of death once again becomes an acute reminder of the precious nature of breathing. How could one be bored or distracted when we practice something so miraculous, so essential?

Mr. Duffy lived a short distance from his body.

From The Dubliners, by James Joyce

Joyce’s unfortunate man who lives near his body is a powerful metaphor for existence in age of of industry. Technology pulled us out of the cave, but it also drew us away from our presence within breath and body. As a consequence, we cannot regulate stress effectively, our energy is easily depleted, and we suffer from the negative, long- term effects of stress; living outside the body has terrible health consequences. Breath work is the secret to good health and to the art of Integrative Conditioning, and that is why we begin with respiration.

Do you practice breathing, or go about the day with little awareness of the movement of your breath? Breathing is fascinating because it is the easiest autonomic function to consciously regulate. While we can breath without thought (most of us do this every day and night), we can also consciously choose to regulate breathing, and therefore radically influence our parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. * Proper breathing, by cultivating the connection between the unconscious and the conscious mind, allows us to discover a state of integration and return to our body, inhabiting it without the self-conscious inhibitions, awkwardness or stress emblematic of the modern age.

Aikido practice is a wonderful method to develop mindful breath work. While some might find it easy to learn how to breathe peacefully on a yoga mat or meditation cushion, can you maintain equanimity in difficult situations? Aikido emphasizes a relaxed body in the moment of the attack. The training carries over into daily life, allowing you to remain calm in stressful moments, whether you are arguing with an angry co-worker, your child, or facing a drunken lout in your favorite bar.

Aikido promotes the cultivation of power through proper breathing and relaxation. So we too, begin with the breath. In later journal entries, I will discuss traditional breath training in Japanese martial arts, but I wish to begin with exercises that teach natural breathing. In breath work and martial arts alike, the most effective techniques are the most simple (the corollary is that evidently simple movements contain the most profoundly subtle lessons). There is tremendous potential for the support of health, power and vitality through the cultivation of natural and relaxed breathing. Breathe with pleasure and presence, as if air was the finest nectar; breathe as if each breath is your final, precious inspiration and your outbreath is the very last exhalation.

Discovering the Diaphragmatic Breath: The Gateway to Freedom

Exercise number 1: The Crocodile Belly Pose

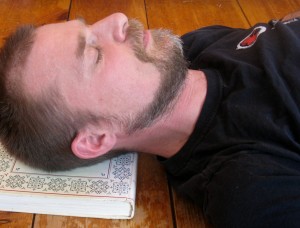

Lie on your belly, with your arms crossed in front of your forehead (figure 1). Take several deep breaths and observe where you feel the breath in the body. When you inhale, you may feel increased pressure on the belly, in particular in the region of the lower ribcage and upper stomach. This may not feel like a particularly comfortable position; you only need to take a few breaths to discover the primary locus of the diaphragmatic breath.

A dome-shaped sheet of muscle and tendon, the diaphragm divides the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. When we inhale, this muscle flattens like an umbrella in the wind, moving towards the abdominal cavity. Simultaneously, the intercostal muscles between the ribs lift the anterior rib cage like a handle on a bucket. The thoracic (chest) cavity expands in all directions, drawing air in from outside. During exhalation, the rib cage releases, and the diaphragm recovers its relaxed, umbrella-like shape. Sometimes this breath is called the “belly breath,” in contrast to chest breathing. The above exercise immediately shifts your focus to your belly and lower ribcage. While you can’t actually “feel” your diaphragm, you infer its movement through the motion of the abdominal and thoracic cavities.

Exercise number 2: Soup in Navel Pose (supine chair)

Now, roll over onto your back, knees a comfortable distance apart, feet on the ground. Most of us will need support beneath our heads (figure 2), rather than the tense position in figure 3, with your chin up and neck exposed. I look a bit stressed; eyes open, forehead creased. See how my cat, Ronin, looks a bit wary, too? For head support and release, I prefer a small pile of magazines or a softcover book below the head rather than a cushion. You should feel like the support allows your throat to soften as the back of the neck lengthens and releases, your chin falling towards your chest. Close your eyes by releasing the forehead, softening the surface of your eyeballs, and gently let your eyelids fall downwards. Place your hands on your belly, with the fingers touching your upper stomach and thumbs on your lower ribcage. Feel how the motion of your breath changes the pressure against your hands. You might observe that this position brings ease to your exhalation; like water seeking the easy course, your diaphragm releases towards the spine and the abdominal cavity easily fills the relaxed dome of the diaphragm (figure 4).

Find softness in your breath work; imagine that you are breathing cool air into the nostrils on a cold day, and when you exhale, imagine that you are breathing on a mirror, and you see the mirror condense and fog with the moisture of your warm exhalation. Make the inhalation steady and smooth. Your cat and other nearby mammals will also relax (figure 4); well-being and bodily integration is contagious.

Then find depth within the breath: slowly lengthen your exhalation. If this is easy and you feel like you are moving into a deeper state of relaxation, begin to lengthen your inhalations, too. After about a minute or so, pause between inhalation and exhalation. Long enough so you find deep stillness, but not so long in which you feel shortness of breath, unease or anxiety. Experiment with the length of your breaths, and find a sense of spaciousness and suspension between the breaths.

If you practice, you will find that is easier to discover a place of profound quiet and return to that place, even in your more agitated moments. I find that the memory of this state calms me when I am unable to practice breath work. When you are ready, roll to your right side, in modified fetal position, eyes closed. Stay in this position for at least a minute. Slowly open your eyes without focusing on any object (it is helpful to only open one’s eyes partially at first). Stay in this position for while, and then roll into cross-legged position. Take a few more deep, soft breathes before going about your day. Or better yet, sit for 15 -45 minutes of meditation.

As you continue our practice of Aikido and breath work, you will also cultivate a deeper connection to the world around you.

Breathe in and let yourself soar to the ends of the universe;

breathe out and bring the cosmos back inside.

–Morihei Ueshiba, the Founder of Aikido

* In a nutshell, the SNS regulates quick response and action- think the flight/fight/freeze response, and external stimuli, whereas the PNS pertains to withdrawal, return to homeostasis, and the processing of internal stimuli. Future journal entries will explore other methods of positive SNS regulation.

The next Integrative Conditioning column will be on developing leg strength, balance, and spinal integration by practicing “The Heron Pose: cultivating leg power, balance and body alignment through independent legwork.”

Benjamin Pincus is the Chief Instructor and Executive Director of Aikido of Champlain Valley. Located in Burlington, Vermont, Aikido of Champlain Valley is a 501c3 non-profit dedicated to creating a sustainable community and peaceable world through the study of the traditional Japanese martial art of Aikido.

Visit us on the web at www.burlingtonaikido.org

As I say reading this I f one myself consciously slowing my breath, taking deeper breaths and pausing between breaths. I could probably even make practice this at work. I’ll be waiting to read the next installment.

Thanks

Let’s try this again and feel free to delete my earlier response.

As I sat reading this I found myself taking deeper breaths and pausing between breaths. Just being more aware of the act of breathing. I think this is something that I could even practice at work.

I’m looking forward to the next installment.

Thanks

Henry, thank you for the support!

sincerely,

Benjamin Pincus

Good work, Ben. Just a breath can be a very powerful thing.

When I was practicing Aikido for a 3 years in the early 70’s, I was introduced to Misogi Breathing while reading a book by Koichi Tohei. It became part of my practice….emptying and drawing in. 45 years later I am in my kitchen eating a spoonful of thick crystalized honey, and it got stuck in my wind pipe. I could not draw any air in so I pursed my lips and expelled air trying to clear it. Though I could not draw any air it I continued this cycle by contracting my abdomen, ribs and diaphragm more between trying to draw in air. This went on for over a minute until finally was able to start sucking in air. When someone inquires if ever I used Aikido, I reply: “Yes, it saved my life.”

Bob, thank you for your great story!