Some people claim to have been touched by the wings of angels; I guess that I could say that I was tossed, pinned and choked by a playful, spirited imp. I studied with Murashige Sensei at San Diego Aikikai, where he was the assistant instructor under Kazuo Chiba Sensei. I had moved to San Diego in order to join Chiba Sensei’s kenshusei program.

Perhaps I should begin with the legend, because the stories we construct determine much of our understanding of a person’s identity and spirit. Murashige Sensei’s father, Aritoshi Murashige, was a student of Jigoro Kano, the founder of Judo. He eventually left Judo in order to study Aikido with O Sensei. Famous for his skill and intensity as a martial artist, he inspired great fear: “I was so scared, “ Chiba Sensei exclaimed, upon describing Murashige’s visit to Hombu dojo; no small statement coming from someone who inspired a bit of discomfort himself. Murashige Sensei’s father must have had tremendous presence; according to the stories, even petulant babies stopped crying when he walked into the room, as if they instinctively sensed a predator.

Many tales are quite dark. Apparently, Aritoshi Murashige was an executioner in the Japanese army during the occupation of China. As you might imagine, he subjected his sons to intense methods of martial instruction. Murashige Sensei said little about his father, but when asked how he learned aikido, he said in his typically droll fashion “I would go to school and get beat up all the time. I go back to my father, learn more aikido, and get beat up half time. Then I learn more aikido, and no one wants to fight me.”

I have heard many stories about his son, too. When Murashige Sensei moved to the U.S., he took bets in bars, challenging people to fight. It was easy money. Inevitably, people placed their bets on the brawny American barfly rather than the diminutive, retiring Japanese man. Or there is the story about his mugging in Central Park, back in the days when Manhattan was a combat zone and Japanese tourists were known to be easy marks due to their tendency to carry large quantities of cash. Sensei hardly knows any English, but he holds up his watch: “You want this?” he asks. When the thug’s eyes shift to the fine watch, Murashige Sensei uses uraken uchi with the same hand, smacks him in the face, and casually walks off.

I mention these stories because Murashige Sensei belied his father’s fierce legacy and martial past with his joyous, idiosyncratic spirit. The reader may imagine a pretty tough character, but Sensei was droll, playful, often smiling, always mischievous. In a dojo noted for its martial intensity and serious, rigorous practice, Sensei was the dojo jester. While we nervously ran about cleaning the dojo, washing dishes or attending to Chiba Sensei, Murashige Sensei chatted away like a schoolboy on vacation. I recall him putting a drop of cream in Chiba Sensei’s whisky when Chiba Sensei briefly left the table during a Friday night dinner. And then, like a little boy, he snickered, with that wonderfully complicit smile on his face.

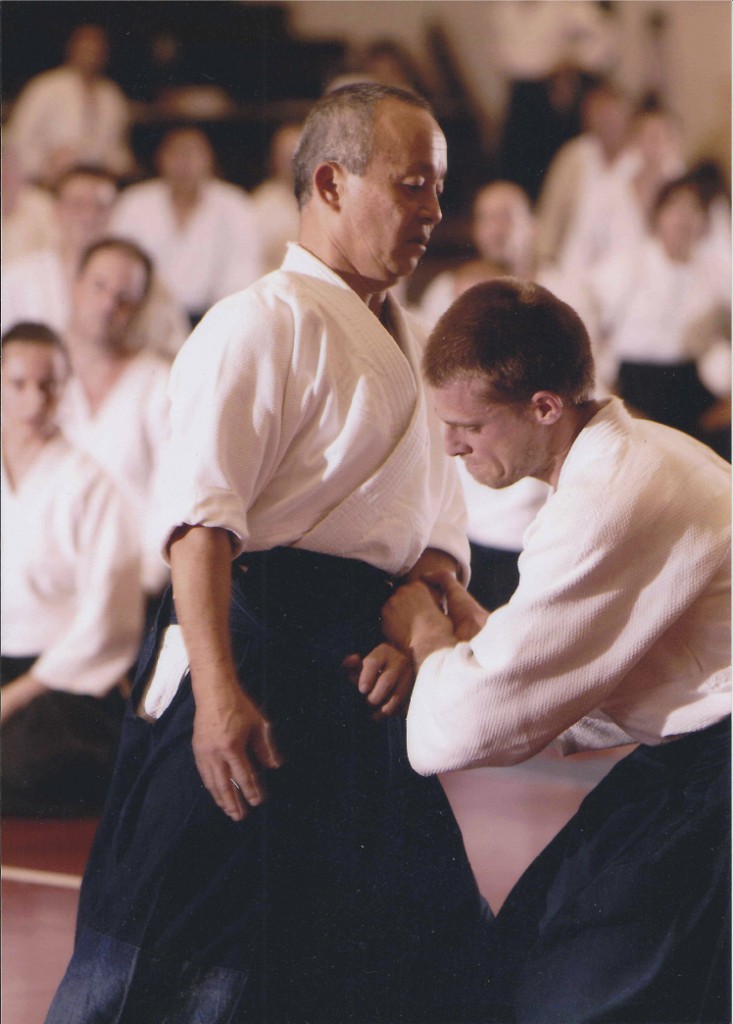

Murashige Sensei described getting thrown by O Sensei as something magical and mysterious: ”One moment standing, next moment down.” He said that he had absolutely no idea what happened and how the world shifted. Similarly, Murashige Sensei’s ki was an inexplicable force; a small, lean man, his power seemed to come out of nowhere. If you capture his technique in the stillness of a photograph, it may look like he was a bit off balance, a bit lackadaisical. But his casual mien and small frame belied tremendous internal strength, timing, and subtly. His shoulders were relaxed and free of tension, and his hands, soft and extended, as if ready to hold a baby. Or strike you hard in the gut. He also threw with great power and ease: his iriminage had the studied casualness and virtuosity of baseball great Sadaharu Oh batting against an easy pitch (Sensei would have me take ukemi in iriminage by blocking his throw with my arm to reduce the chance of injury). * Soft power, he would call it. I had felt nothing like it before.

Do I believe in magic? If I define magic as a sense of wonder in the face of the inexplicable, then I suppose Murashige Sensei had magic (if he was still around, he would correct me, call it “The Power” instead, and toss me several times for good measure. His technical skill and ability to relax allowed him to access a surprising amount of power, in particular given his slight build. In my experience very few of his sempai, including uchi deshi of the late Doshu and O Sensei, seemed to access to this kind of internal power. I suppose he led a charmed life in other ways, too.

Sensei had a heart condition caused by contracting Kawasaki disease as a child. This ailment, if untreated, often claims its victim early in life. Apparently, he lived with this condition longer than anyone else in the U.S. I often wondered if his perennial good cheer had something to do with his awareness of his mortality. Why focus on oblivion when you can practice Aikido, laugh, love your family, drink beer, prepare sushi, and eat good food? What more is there in life?

I mourn the passing of a great teacher. I have so many memories. How he would catch my center in ikkyo, and down I would go. He would manage a quick kick to the solar plexus for good measure, whisper something mysterious, and smile when I rose to my feet. I remember training with him for a full hour when Tamura Sensei came to San Diego. Years after I left San Diego, I recall Sensei, beer in hand, demonstrates a “no inch punch” on M.D at a dojo party. M.D. is a big man, now in the Special Forces. He is standing, braced in a stable hamni position, and Sensei is still in his chair. He knocks M.D. back several feet without spilling his drink. His emphasis on internal power, spontaneity and organic movement wonderfully complemented Chiba Sensei’s technical precision.

Once Murashige Sensei earnestly explained his secret: “Heavy Hand. I finally discovered The Power,” as if it were so simple and obvious (he also provided the esoteric explanation that “Chiba Sensei’s power comes from here” – pointing at his thumb – and “my power comes from here” – he wiggles the base of his little finger). Even Chiba Sensei, a direct student of the late Doshu and O Sensei, would tell us that we should study with Murashige Sensei: “learn from him – he does things that I cannot do.”

I recall his droll amiability, and of course, that deadly, relaxed iriminage, with so little muscular effort, and so much energy. I remember his quick atemi (strikes) and his sutemi waza classes: crazy sacrifice techniques out of nowhere, a peculiar amalgamation of Judo and Aikido, and then that impish smile as I stand once again. It was hard not to smile despite the intensity. Heavy hand, light heart, and a lot of ki. Sensei, good luck on your final journey. Thank you so much for your wonderful spirit and profound instruction.

* Sadaharu Oh broke the world record for the number of home runs: 868 home runs during his baseball career in the Japanese major leagues. Famous for his flamingo-like batting stance, he held his right leg tucked high in the air before the pitch. Oh studied Aikido to improve his batting skills, and attributed his tremendous success to his Aikido practice. This “flamingo leg” stance was notable due to the fact that it required tremendous confidence in his ability to maintain his balance despite the fundamental instability of the position. Similarly, Murashige Sensei sometimes appeared off balance due to his extremely relaxed, internal method of Aikido. But his body was so integrated, allowing him to throw with great power and minimal effort. I have often been thrown by people with significant body mass and muscular power, but it feels very different to experience power from a person of slight stature like Murashige Sensei.

A brief biography:

Born in Yamaguchi-ken in 1945, Murashige started Aikido practice as a teenager with his father, Aritoshi Murashige. He moved to Tokyo to train at Hombu dojo with Morihei Ueshiba and others including Seigo Yamaguchi, Yoshimitsu Yamada, Kazuo Chiba, Mitsunari Kanai and Terry Dobson. He cited Yamaguchi Sensei as a major source of inspiration. He taught at New York Aikikai with Yamada Sensei for three years starting in 1965 before returning back to Japan. He returned to San Diego, where he worked as a sushi chef. In 1981, he also taught at San Diego Aikikai with Chiba Sensei, a direct student of the Founder. He left San Diego Aikikai to teach at Jiai Aikido of San Diego, and taught his last Aikido class ten days before his death on October 11, 2013.