Empty-handed I entered the world

Barefoot I leave it.

My coming, my going –

Two simple happenings

That got entangled.

(Poem brushed by Zen Roshi Kozan Ichikyo on the morning of his death, 1360)

It is late at night, and my father is gone. I wander through my parent’s house, looking for something to hold on to in the face of his absence. Apart from letters, I find only these concise, lapidary notes:

Went to Brown because the grass looked like Ebbets Field at night

1960 Jane and I marry and go to Italy on a Fulbright

1961 Graduate School at Harvard in Philosophy

A Brooklyn Dodgers fan, my father lived ten blocks from Ebbets Field. In 1947, when Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier as the first African American in the Major Leagues, my father cheered from the bleachers. I don’t particularly like sports; my mind clouds when people discuss favorite teams, but Robinson’s victory wasn’t about bats and balls, wins and losses; it was a historical happening, a prelude to the great civil rights movement that was to transform our nation.

I am haunted by his words: I “went to Brown [University] because the grass looked like Ebbets field at night.” It is strange how seemingly fickle decisions dictate the entire watercourse of one’s life.

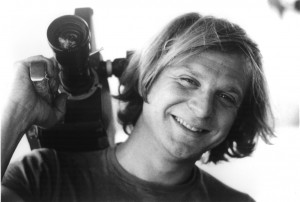

If he had the time to continue his biography, he might describe a trajectory from Robinson’s home run on Ebbets field to his growing social consciousness and artistic vision. He became a pioneer of cinema vérité documentary filmmaking, following the civil rights movement in Natchez, Mississippi (Black Natchez) and many other films in which the personal and political are entangled. My father also taught film at MIT and Harvard, and became a cut flower farmer in Vermont. He was in the process of completing a film, “One Cut, One Life” at the time of his death.

Because the grass resembled Ebbets field, he meets my mother at Brown University, and later fathers two children, my sister, Sami, and then me. The summer I turn thirteen, Gary, a family friend and my dad’s former MIT film student, demonstrates Aikido on our front lawn in Roxbury, Vermont, 50 feet from the room where my father breathes his last breath. I learn how to forward roll that summer. And after another 13 years of rolling (with some time away for various youthful pursuits), my father introduces me to a vibrant young aikidoka named Heidi, who later becomes my wife.

This all happens because a lawn evokes nostalgia for a fucking baseball field. I simultaneously feel anger and wonder at this absurdity. I cry as I write. I grieve because I have lost my father, and also because I celebrate the extraordinary vicissitudes of karma, the magical convergence of will and inevitability. I cry because without these entanglements and connections, I wouldn’t write this eulogy. I suppose I could say if it weren’t for my father’s longing for Ebbets Field, I wouldn’t exist.

My father came to Aikido relatively late in life. At the age of 44, he taught documentary filmmaking at Harvard University. We began our practice at the Harvard Aikido Club. I realize with a start that I am now the age of my father when he first discovered Aikido.

Aikido was a revelation for my father. He once said that until he discovered Aikido, he learned everything by reading. An autodidact, he learned philosophy, mathematics, how to fix a tractor, grow garlic, flowers and ginseng from books. So he immediately purchased this gorgeous book (slip-cased, hardbound, with cool drawings and diagrams) called “Aikido and the Dynamic Sphere.” He read with the avid devotion of an initiate and with the critical discipline of a philosophy major, cover to cover. “I didn’t understand a word of it,” he told me with pride, and never picked up another book on Aikido again.

My father loved Aikido because it was the first physical exercise that he discovered that was infinitely fascinating. To this day, his childlike enthusiasm and perpetual wonder at Aikido inspires me in my critical moments. He also discovered how its lessons transcended physical practice. The relaxed, efficient movements of Aikido made him a better filmmaker; his style of filmmaking emphasized minimal equipment and mobility, which meant that he needed to hold his body still rather than use a tripod. He would teach his students how to pan and turn with the camera using the principles of Aikido.

I must admit that I didn’t always enjoy practicing Aikido with my father. He was quite stiff and liked kyusho jitsu (pressure point techniques) and tricks: a painful finger into the temporal mandibular, a knuckle behind the ear. But his Aikido changed as his body began its decline.

Four years ago, my father was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. One hand in particular would shake and twitch. But his tremors disappeared as soon as he stepped on the mat. Somehow, his devotion to Aikido and his single- minded focus provided his body with strength and vital energy. His center seemed as strong as ever. I was reminded of the Roethke poem: “This shaking keeps me steady. I should know…I learn by going where I have to go.”

Parkinson’s seemed like a walk in the park after my father was diagnosed with the blood disease myelodysplastic syndrome, which morphed into leukemia. After his diagnosis, it was a revelation to train with my father. He could no longer take falls; it was too risky given low platelet levels, and a scratch or bruise could have major health consequences due to poor clotting and a weakened immune system. So I gently practiced tai sebaki (body movement), and he would throw me. His Aikido had a soft intensity, sensitivity, and presence. He had discovered a joyful state of awareness born from his knowledge that his time was limited. One cut, one life: we should live as if every moment counts, and as if every moment could be our last.

My father in law, David, is a deeply caring doctor with an infamously blunt bedside manner. He read my father’s blood count numbers and told him that he was a dead man. “Start writing your bucket list,” he suggested.

I was curious. What would I do knowing that I only had a short time to live? My father told me that he didn’t need a bucket list. He felt that his life was full, vital and creative, and what more could you ask for? “I just want do the same things as before, and live with more passion.”

My father had a deep horror at the atrocities committed in the name of organized religion. So he never expressed interest in any conventional spiritual practice. Perhaps he was afraid to die, but I never got the sense that he needed solace in any construct of divinity. As my father got sicker, I realized that Aikido was his spiritual path. His religion was the feeling he got when he felt exhausted from the stress of illness, chemotherapy, and insomnia, and I would grab his wrist and he would smile, as color would come into his face. “My pipes are open,” he would say, describing the flow of ki through his body. I recall O Sensei (the founder of Aikido) saying that Aikido brings all religions into fruition.

My father was a great mentor. When I had problems at the dojo, he listens quietly, his whole being at attention. He tells me a story. He was shooting “Axe in the Attic” with his film partner, Lucia. The movie follows the struggles and exodus of former New Orleans residents in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. A family invites them to a service at a Baptist Church in Pittsburgh. The minister says that everyone is welcome: it doesn’t matter who you are or what you have done, or the color of your skin. He tells me this story because, despite his often skeptical secular humanist outlook, he saw true love in that church. He says that this is the way to run an Aikido dojo, too: everyone is welcome and Aikido is inclusive. I loved my father’s generosity, presence and caring spirit.

A spinal tap reveals that the blasts are in his spinal fluid, creating pressure on my father’s brain. The nurse is blunt: you should go into hospice. It is much better than continuing to get platelets, prolonging your life. If I stop platelets, I would begin to hemorrhage, my father says. From the mouth and nose. The nurse nods, and then explains that he would die from internal bleeding. This is a good way to go. My father, despite the fog of nausea and headache, disagrees. “I have things to do. I need to complete a film, my book, and do a farm transfer.” I smile and I cry at the same time, because this is my father: always ready to create in the face of death.

My father’s condition steadily worsens. He is beginning his final journey, so there is no time to edit his last film, teach me farming, or tell me stories. My sister, Sami, spends the first half of the night in bed with him, and I take the second shift in order to relieve our exhausted mother. He reaches his hand out and I hold it in the darkness. “What time is it?” he asks me occasionally, and I cannot sleep, so I watch the sky turn grey and listen to his struggling breath.

I recall the times he held me as a child, and I feel abandoned. A week before, I had this dream in which he died, and as his spirit left his body, I felt this tremendous wrenching, as if a tether from my chest was forever severed. The peculiar intensity of my dream state gave me the sense that my father’s death marked the loss of my childhood. I awoke with a sob of anguish and a sense of utter desolation.

We move him to a hospital bed. If he opened his eyes, he could see the leafless maples and the green lawn where I learned how to do my first Aikido forward rolls. The sky is so clear. Perhaps, without looking, he recalls the clarity of green grass, and the spectacular red of maple, the creamy yellow hues of poplar. Perhaps he remembers the brilliance of the grass at Ebbetts field when he was only nine years old, and Jackie Robinson goes to bat, stoically enduring racist taunts. How clear and bright everything seems, in that tense stillness before Robinson swings. How much was at stake. One cut, one life.

It is Tuesday, November 5th, and it is unusually warm this late in the fall. I go outside with my family. My wife, Heidi, takes photographs, while my boys and I throw milkweed seeds into the air. Heidi holds an empty milkweed husk in her hand while we scatter seeds to the wind. Some seeds float away, and others land on the ground, where they undulate in the warm wind, like delicate sea creatures neither of this world or another. My son, Caleb, looks up and we watch a barred owl wing his way over the hills beyond. When I go inside, my father’s ki finally leaves his body. There is no breath, no pulse. I touch his wrist, hold his hand, and kiss his forehead for the final time, as he goes on that final, great journey.

The Waking

By Theodore Roethke

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I feel my fate in what I cannot fear.

I learn by going where I have to go.

We think by feeling. What is there to know?

I hear my being dance from ear to ear.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Of those so close beside me, which are you?

God bless the Ground! I shall walk softly there,

And learn by going where I have to go.

Light takes the Tree; but who can tell us how?

The lowly worm climbs up a winding stair;

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

Great Nature has another thing to do

To you and me; so take the lively air,

And, lovely, learn by going where to go.

This shaking keeps me steady. I should know.

What falls away is always. And is near.

I wake to sleep, and take my waking slow.

I learn by going where I have to go.

Yoel Hoffmann, Japanese Death Poems, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1996.

Theodore Roethke, from Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke, Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., 1961.

.

Hi,

I read your story and have been moved. I found it by googling Mental Presence, am a yoga breath meditation teacher. I live in Israel and am a mother of 7 children and more than 20 grandchildren so have been very blessed, like you. I studied Tae Kwon Do and attained a 1st degree and then Aikido a little, so can relate to you, your father. You have a beautiful way of sharing and well just thank you so much for sharing a little of his rich life and your perceptions….Best of everything, Rivka

Dear Rivka, thank you very much for your appreciation.

sincerely,

Benjamin Pincus

Dear Ben,

I practiced with you and your dad many years ago in Roxbury. I was very fond of him and your mom Jane.

I was saddened to hear of his death recently from Chris Nathan, a former student of yours.

I discovered that he filmed a documentary about his final year, ‘One Cut, One Life.” If there is any way I can obtain a copy of the documentary I would greatly appreciate it.

I hope you and your family are well and thriving.

Ralph

Ben- I read and cried. Thank you for the beauty of your writing telling your fathers story. For sharing a little of your life. I wish I had your skill to have written on Sugano’s passing. I lacked the language and pathos your writing carries and mine was rude by comparison. I wish I had met your father. If he was half as remarkable as you make him to be he was indeed remarkable.

Thank you for this beautiful story.

Gassho-

Brian

What beautiful words to remember a father. “I learn by going where I have to go.” A man who lives his passion and his related story reported for his son leaves an impression on our soul. We are all sons or daughters and many of us are parents. Your father, wherever he is, is proud of you. Thank you Ben for sharing these beautiful words and experiences.

Dear José, thank you for appreciation and gratitude! May the good qualities of our parents live on in our psyche, and may the challenging qualities fuel our search for perfection…..and perhaps, help us accept our fundamental lack of perfection, too.